OCA

Photography level 2

Digital Image and Culture

Part 3: We are all photographers now.

Assignment 3:

What is your understanding of the ‘digital self’ and what is the effect of our everyday use of photography upon it. Discuss using relevant case studies and published research.

OR

Would Janus take make a selfie?

Word count: 3329

Quotations 605

Total 2724

Illustrations:

Figure 1:

Penelope Umbrico: Suns from sunsets on Flick’r (2006) Page 9

Figure 2:

My image of Erik Kessels’ ’24 hours of images.’ Page 11

Figure 3:

A Kim Kardashian selfie. Page 13

What is your understanding of the ‘digital self’ and what is the effect of our everyday use of photography upon it. Discuss using relevant case studies and published research.

OR

Would Janus take make a selfie?

The theory underpinning this essay is taken from Guy Debord’s ‘Society of the spectacle’ and in particular thesis 13: “The basically tautological character of the spectacle flows from the simple fact that its means are simultaneously its ends. It is the sun which never sets over the empire of modern passivity. It covers the entire surface of the world and bathes endlessly in its own glory.” (Debord 1970:13)

The guiding questions are: What constitutes the digital self and could a photography exhibition change the way we look? Why involve Janus, a Roman mythical god, in discussing photography in the 21st Century?

Janus was the double-faced god of beginnings, endings, gates, doorways, passages, time and transitions. In houses he was often put facing external doors to protect the household from disasters. In the Pompidou Centre, that very visible, endlessly photographed example of post-modern architecture in Paris, the images on both sides of a board hanging in the central market hall are those of President Pompidou. Facing in opposite directions, they signify a transition or passage from the modern to something beyond it. When it was built in 1970, one of the principal architects, Renzo Piano, said that the design concept was based on a medieval market place where, on the interlinked and intersecting layers of spaces, people would meet and talk. So we have a paradox of an ultra-modern expression using a medieval concept as a vehicle to ring in the revolution-avoiding socio-political changes so necessary in France post May 1968.

In his 2013 publication, Martin Lister includes the essay “The digital image in photographic culture” by Rubinstein and Sluis in which they introduce the Janus principle :“Like a two-faced Janus, photography points in two directions at once: one side faces the objects, people and situations as they appear in the ‘real’ world, and is occupied with the representation of events by flattening their four dimensional space onto the two dimensional plane of the photograph … the other side points towards photography’s own conditions of manufacturing, which is to say towards the repetition and serial reproduction of the photographic image.” (Lister p. 25) This essay will show if or how this illustrates aspects of the digital self by identifying the transition moments and the ways in which the new medium has formed and adapted how we look, meaning both how we appear and how we see. The work used to substantiate the points made are the photography of Penelope Umbrico and Erik Kessells, the manifesto of the 2011 Rencontres d’Arles exhibition and the 2012 paper Selfiecity: exploring photography and self-fashioning in social media by Tifentale and Manovich (9).

To Martin Heidegger in 1977 is ascribed the observation that “representation is the key characteristic of the modern age” in which “ the world becomes a picture and the human being becomes a subject.”(Lister p.25) Heidegger goes back to the 17th Century, to Descartes who maintained that representation was the marker of modernity because it concerned itself with truth founded on rational and abstract principles rather than on subjective or aesthetic ones. Descartes was talking in scientific terms where experiments could be repeated and the outcomes could be represented in diagrammatic form, without any subjectivity or aesthetics involved. In making the assumption that humans are rational and capable of objectifying the world of knowledge in graphs and diagrams, he makes us consider the converse, that humans can express themselves in subjective, aesthetic, artistic and metaphysical terms too. The ontology of photography has been based on the visual representation of the science of optics, the mechanics of automatism and the objectivity of rational representation. Logically, this all gave photographs, created by a rational human author, the credibility of having transferred reality from the object to its re-presentation. With the advent of digital photography, based on the binary system of computer language, we would expect that that scientific quality would sustain the idea of objective representation operated by a rational human to produce objective, credible, reproducible representations. This is supported by that sage of all photographic sages, Roland Barthes who states: “The photograph is literally an emanation of the referent. From a real body, which was there, proceed relations which ultimately touch me, who am here.” (Barthes, 1981:80). Those who are au fait with dark room photographic practices as well as with digital algorithmic capabilities, know that people are involved in the production of an image, be it on paper or on the screen and that the process, therefore, will involve more than just scientific, mathematical or rational principles.

In his documentaries entitled “The Century of the self,” (2002) Adam Curtis illustrates how the consumer-led policies of the early 20th Century are still in place today in the USA and in the rest of the industrialized world. The series focuses on how the work of psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud was used by business and politicians to read and fulfill created desires to control the masses, develop consumerism and how people saw themselves. The prime protagonist in the series is Edward Bernays, Freud’s nephew, who picked up on Freud’s contention that people are irrational and that if you pander to their selfish desires, tap into their deepest fears, in every field, they become docile and malleable. Furthermore, if you could link a product to their emotional desires and feelings you could persuade people to behave irrationally believing that they felt better for buying a certain product. The late 1920’s saw the flourishing of consumerism in the USA, the start of political spin and the commodification of Hollywood and its celebrities, and the Wall Street crash. In an interview following the death of Marilyn Munroe in 1962, playwright Arthur Miller maintains that rather than freeing man, consumerism was controlling and defining him and that it was part of the power-mad ideology of the times.

Elaine Glaser, author of Get Real: How to see through hype, spin and lies of modern life states “ When every person in a train carriage is staring at a small illuminated device, it is an almost tacky vision of dystopia. … Technology – along with turbo-capitalism – seems to me to be hastening the cultural and environmental apocalypse. The way I see it, digital consumerism makes us too passive to revolt or to save the world.” This illustrates precisely what Bernays was trying to create in the 1920s, and what debord maintained regarding the character of the spectacle. To complete the picture, in the 1950’s, Theodor Adorno wote in The Dialectic of Enlightenment: ‘Not only do we have the freedom to choose what was always the same, but, arguably, human personality had been so corrupted by false consciousness that there is hardly anything worth the name any more. “Personality,” they wrote, “scarcely signifies anything more than shining white teeth and freedom from body odour and emotions .’(Jeffries)

Psychologist Dr Tamara Hicks claims in an article of 2010 that we all have a ‘digital mask’ to engage with the technological world. She goes on to identify the plethora of internet technologies which had been introduced and to which we can add so many others which surface daily under the conceit of digital culture. Hicks observes “… All of this technology has come at us so fast and furiously that we haven’t had the time to think about how our relationship with it shapes our very identity.”(PT) It seems, therefore that the ‘digital self’ is under constant change and that we, the ‘self’, are not aware of who we are any more.

Despite the fact that we know how we are being manipulated to keep capitalist fires burning, we continue to define ourselves, unwittingly perhaps, by the information we upload to all the sites of which we are subscribers. Do we know who picks up our information, where in the world or why? Not really. The groups we belong to on Facebook and other social media websites, the ‘private’ conversations on Whatsapp or Snapchat, the searches we make on the internet, the items we purchase online, the articles we post or repost or share on social media all become part of the complex algorithms which define our composite selves and ‘know’ us better than we know ourselves. All the information is fed to commercial enterprises which then target us using the information we have voluntarily given up. The ends are the means.

The manifesto, written by Erik Kessels, one of the curators of the 2011 Rencontres d’Arles exhibition (appendix 1), illustrates how they felt about the opportunities afforded to consumers following the internet revolution which had been in its infancy barely twenty years previously. Its linguistic style is reminiscent of the Futurist manifesto which appeared in 1909, and observers might be forgiven for thinking that the 2011 one is a parody of its predecessor. It is very assertive by marking the changes starting with the adverb and punctuation mark “NOW,” and “ABSOLUTELY PRESENT.” In the present , and the future by implication, things relating to photography are and will be different. The translation of the prose part of the 1909 Futurist manifesto reads: “With it, today, we establish Futurism, because …” (Italianfuturism.org).

The pronoun ‘We’ occurs in both manifestos and is emphatic in both. Although the ‘We’ in the 1909 manifesto refers only to one (Italian) man, Marinetti, the ‘WE’ in the 2011 manifesto refers to five European men, 4 of whom are established in the canon of professional photographers and one a professional curator. Given the background of the co-signatories of the 2011 manifesto, is it legitimate to feel that their ‘WE’ resents the intrusion onto their professional territory of every amateur Tom, Dick and Harry photographer using any conceivable image making product and scissors?

There is in both manifestos an emphasis of a separation from the past “WORK THAT HAS A PAST BUT FEELS ABSOLUTELY PRESENT”(Appendix 1.) “Our fine deceitful intelligence tells us that we are the revival and extension of our ancestors—…”(Futurist manifesto)

The curators have gone beyond the question ‘Is everyone a photographer?’ the photography equivalent of the 1975 Joseph Beuys poster “Is everyone an artist?‘’ because it states “ WE ALL RECYCLE, CLIP AND CUT, REMIX AND UPLOAD” which also implies that we have all gone beyond taking images, we now make images in a myriad ways and all under the umbrella of digital photography. Furthermore, in the introduction to the Arles 2011 catalogue, Clément Chéroux, curator of the Pompidou Centre and co-writer of the manifesto, claims that the importance of images has gone from ‘newness’ to ‘intensity’. In clipping and cutting (frivolous, reductive terms explaining how images are ‘made’ today), we are no longer stealing someone else’s work because the images are seen as collective cultural property and the astronomical numbers of images uploaded daily make the practice of sorting through them appear as an OCD, a madness, a loss of rational behavior taking away from the serious expertise, intentions and authorship involved in the original images.

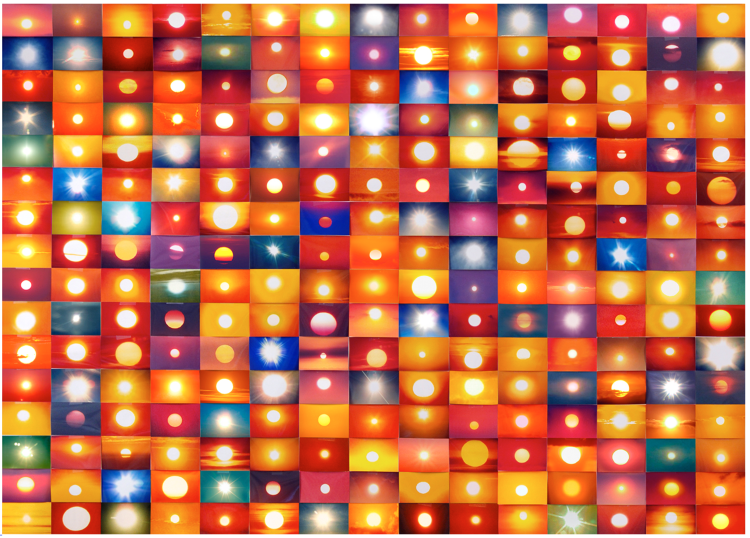

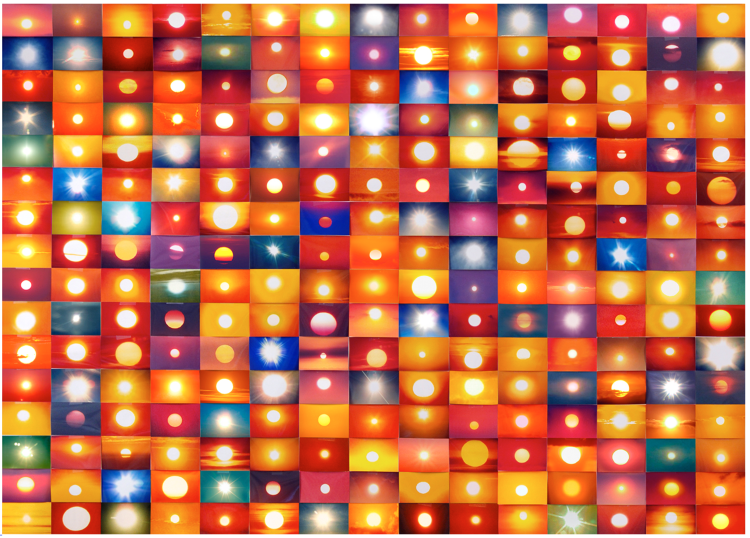

One of the artists on show at the Arles 2011 exhibition was Penelope Umbrico whose work is eye-catching and constantly evolving. She defines herself as “an artist whose subject is photography. …It has expanded beyond the field and there are very few boundaries –”(Martin 3.2) Her most famous work is Suns from sunsets on Flick’r which started in 2006 and is on-going as more sunsets are added to the website.

Figure 1:

Her work deals with the flood of images, in this case of suns on Flick’r, which are uploaded without any reflective or critical judgement. Through her work, Umbrico asks us to reflect on the role played by image making and image makers in an image-saturated world. Having claimed that, Umbrico goes on to make yet more images of the over-imaged which seems to contradict her initial premise.

Although in her MA thesis on Umbrico, Minjung “Minny” Lee writes about ‘visual ecology’ which, as she explains in a footnote, was a term coined by Juan Fontcuberta (also one of the Arles 2011 manifesto contributors) to mean “the activity of artists appropriating found photographs instead of making new photographs. This recycling of images actually helps the environment, as it does not take up any new server space.” (idem) . Is the space not doubled every time an image is appropriated because it now exists on yet another server space? Umbrico and Erik Kessels continue to make work that questions our online photography behaviour making us pause to think about what our actions show about us and about society in general, how our actions impact on our constantly changing perspectives on ourselves and society. As the manifesto implies, we can make limitless images which we can ‘share’ with the world and nobody can limit our production. There is no more need for the focus groups analysed in “the Century of the Self” because all the information needed by policy makers and corporate companies is there for anyone to use.

In using the grid format to present her work, Umbrico does not present a narrative we can read in sequence and interpret. Instead, the reading of the composition takes us beyond the limits of the grid frame to wonder where all these representations of suns are taking us and why we have this compulsion to make images of sunsets to then upload them. If there is an entry point into the sun grids it is not clear. What does it say about those who upload the images? Who are we collectively? How many ‘likes’ and ‘shares’ do we want for our images? Umbrico sees the abundance of visual information on the internet as “a visual index of data that represents our collective thoughts, ideas desires and so it is a constantly evolving and spontaneous auto-portrait.” (Martin p. 3) The more we interact with the media and the technology, “the more they function as indexical records.” (idem)

The exhibition at the 2013 Rencontres d’Arles by Erik Kessels’ “24 hours of photos”, presented the same problem as Umbrico’s practice does. Kessels printed the million images which had been uploaded on to social media in a day and dumped them in a room of the Palais de l’Archevêché. Does this represent visual ecology too?

Figure 2:

My photograph of the Erik Kessels room at Rencontres d’Arles, 2013

The installation resembled an avalanche of images about to obliterate the viewers – do we go beyond admiring the idea and its execution?

The multi-disciplinary team which worked on the Selfiecity project in thirteen global cities, analysed the demographics, the poses and expressions of those taking them. A selfie, according to Oxford Dictionaries, is “a photograph that one has taken of oneself, typically one taken with a smartphone or webcam and uploaded to a social media website.” Jenna Wortham of the New York Times calls them “a “virtual “mini-me,” what in ancient biology might have been called a “homunculus” – a tiny pre-formed person that would grow into the big self.” (7). Also relevant to this essay is an attitude of Karen Nelson-Field, author of Viral Marketing: The Science of Sharing (Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press, 2013): “We now all behave as brands and the selfie is simply brand advertising. Selfies provide an opportunity to position ourselves (often against our competitors) to gain recognition, support and ultimately interaction from the targeted social circle. This is no different to consumer brand promotion.” (7) Debord would simply say QED at this point.

Apart from falling prey to the self-promotion, self-revealing ploys of online quizzes and other ‘fun’ social media activities, selfies express in current technological form what pen or paint portraits did in the past and reflect the revolution in snapshot photography for the masses associated with the Kodak Brownie camera introduced in February 1900.

In a dossier on the selfie in the 2014 January-February edition of Fisheye, it states that ‘selfie’ was first used in 2002 on an Australian online forum, and the ‘♯selfie ‘ in 2005 on Flick’r, but its usage did not take off until 2012 and accepted in the online Oxford dictionary in 2013. The same article states that celebrities are a step ahead of other mortals and quotes Justin Bieber who ‘selfied’ his tattoo, his six-pack, himself with a groupie, with his blond girlfriend … until eventually, the article states, “The singer quickly understood how to make people talk about him and how to make business.” (Fisheye p. 27 – my translation) In 2013 he invested $1.1 million in the app ‘Shots of me’ which allows users to make, to share, to like and to geolocate images of themselves. Kim Kardashian (10) also posted advice, it states, on how to take the perfect selfie … with pout. Last year she published a 448 page book of her selfies which sold 125,000 copies in the first three months. ( 11).

Figure 3:

Kim Kardashian selfie with pout:

Tumblr joins the circus with sections on selfies taken in serious places like at funerals (Obama, Cameron et all at the funeral of Nelson Mandela) and in front of books in a library.

The passage from old to new in photography seems to have been marked by, inter alia, the 2011 Arles manifesto reflecting a decisive shift to the ‘cut, clip, remix and upload’ (appendix 1), where you no longer needed to be a professional photographer but ‘a species of editor’ (Appendix 1) (pejorative?) to show your photographic work to the world. This work ‘that feels like play’ like that of Penelope Umbrico which was exhibited at Arles in 2011, has a serious critique of those unfettered practices lacking self-checking controls. Does the supposition that it feels like play mean that it lacks the gravitas of previous photography? The acceptance of the word ‘selfie’ in the Oxford dictionary in 2013 gives legitimacy to a practice which confirms unbridled digital self-promotion apparent on social networks which, sustained and abetted by new technologies, replicates and sustains those advertising practices started in the 1920s by Edward Bernays to ‘turbo-boost’ consumerism. Commerce sees the ‘homunculus’ grow, in certain respects, daily, as do their profits.

It seems that the period between 2011 and 2014 was that pivotal time in photographic history when change set in; when social media, engendered by technology, allowed digital practices to mark a shift in people’s online behaviour and when selfies did not constitute our only indexical selves. It also signifies a time during which corporate companies adapted to these changes and continued using consumer profiles to boost sales. Unable to resist consumerism and conformity, whether seen as a rational Cartesian being or an irrational, fear-ridden Freudian consumer, the self occupies centre-stage in representations of the world, regardless of audience and becomes its principal subject. The digital self is branded by capitalism, time, technology and social media.

Janus, an all-seeing mythical, irrational god, still stalking our post-modern, would not take or make selfies, in my opinion. As god, he does not need to promote himself, he does not need to fight for supremacy in his community of one, his status never changes. As such, he does not need our ‘like’ or ‘share’ or the subjective aesthetics of Kim Kardashian, she of the (absence of) white teeth and free of body odour, to boost his self-images. Can he of ancient Rome protect us from our cultural apocalypse?

References:

Bibliography:

Barthes,R. 1981. “Camera lucida: Reflections on photography. London, Vintage.

Debord, G. 1970. The society of the spectacle. AK Press.

Lister,M. (Ed) 2013. The photographic image in digital culture. Routledge.

Martin, L.A.(Ed).:2011. Penelope Umbrico, Photographs. Aperture Foundation.

Hebel,F. (Ed.): 2013: Arles in Black. Rencontres d’Arles

Articles:

Gergel, J. 26/01/2012. From here on:Neo Appropriation Strategies in Contemporary Photography. Interventions Journal Arles 2011.

Jeffries,S.: 09/09/2016. Why a 1930s critique of capitalism is back in fashion.

Fisheye: janvier-février, 2014:Dossier: le selfie pour tous.

Websites:

- https://schmid.wordpress.com/2011/06/28/from-here-on-les-rencontres-darles/from-here-on-indd/

- https://interventionsjournal.net/2012/01/26/from-here-on-neo-appropriation-strategies-in-contemporary-photography/

Appendices:

1.

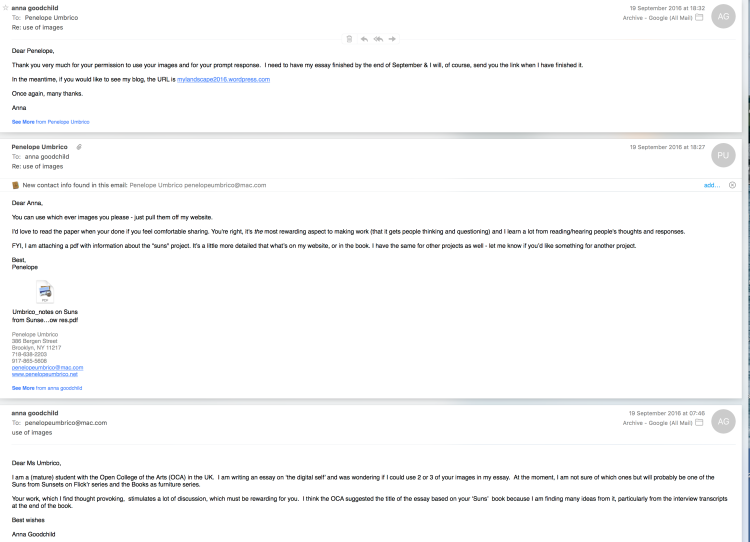

2. Penelope Umbrico : email:

3. Penelope Umbrico PDF: umbrico_notes-on-suns-from-sunsets-from-flickr-and-related-work-2006-ongoing_low-res

3. Penelope Umbrico PDF: umbrico_notes-on-suns-from-sunsets-from-flickr-and-related-work-2006-ongoing_low-res

Self reflection:

What went well:

- Reconnecting with Janus & finding the serendipity of 1 of the writers of the Arles 2011 manifesto linked to the Pompidou Centre which linked to Janus!

- Linking very contemporary articles with 17th century thinking.

- Discovering the ‘selfie’ research & how it could link with the essay.

- Discovering the breadth & depth to Penelope Umbrico’s work.

- Discovering the 2011 Arles manifesto & linking it to the Futurist manifesto which changed my attitude to the 2011 manifesto: I initially took it at face value but, when I analysed the language used, I came to a very different conclusion.

What could have gone better:

- I found I was rushing the work because I had so much else on.

- I wish I could have spent more time investigating Kessels’ work.

Assessment:

Demonstration of technical and visual skills: Not needed in this assignment.

Quality of outcome: It’s not perfect but the aims tied up with the conclusions.

Demonstration of creativity: In using Janus to tie the whole essay together.

Context: Adequate contextualization of the salient points analysed.

Tutor’s report

As ever, Clive’s report came, swiftly and concise:

Overall Comments

A convincing piece of work.

Feedback on assignment

I’m not going to quibble about the arguments, not that I’ve got anything substantive to say on that scored. It’s intelligently argued using interestingly selected resources and research.

The Janus theme was a very good idea. You’re obviously accomplished at constructing evidenced written arguments.

The only point I would make is about structure. You need to make it easily consumable at assessment so break the text up in to smaller ‘bite sized’ ideas and some subheadings would be useful.

You might consider beginning with a bullet list which lays out the structure of the document and hence your argument.

As an assessor I’ve always found it useful to know where I’m being taken and why before we set out.

Also it might be an idea to get someone to proof read it.

This is something I spotted, it maybe intentional it may not,…

‘Janus, an all-seeing mythical, irrational god, still stalking our post-modern, would

not take or make selfies, in my opinion. As god…’

Should it be ‘post-modern world’ and ‘As a god’?

Coursework

All fine

Research

Ditto

Learning Log

All tickety boo now.

Suggested reading/viewing

You know what you’re doing and what you need, carry on.

Pointers for the next assignment / assessment

You’ve already suggested an idea to me so let’s see where it goes. Any advice you need in the interim please email me.

I have every confidence in your abilities.

Reflection on the tutor comments:

I feel that the comments are very relevant and leave no doubt as to what I should do which I hope will be reflected in my reworked essay below.

Revised assignment:

The contents page, the references i.e. bibliography, websites, magazine articles & appendices etc have not changed so I will not replicate them here.

What is your understanding of the ‘digital self’ and what is the effect of our everyday use of photography upon it. Discuss using relevant case studies and published research.

OR

Would Janus take make a selfie?

Theoretical structure:

Guy Debord’s ‘Society of the spectacle’ and in particular thesis 13: “The basically tautological character of the spectacle flows from the simple fact that its means are simultaneously its ends. It is the sun which never sets over the empire of modern passivity. It covers the entire surface of the world and bathes endlessly in its own glory.” (Debord 1970:13)

The guiding thoughts and questions:

- The passivity and self-referential qualities are encouraged by social media (with a strong consumer bias).

- What constitutes the digital self?

- Why involve Janus, a Roman mythical god, in discussing photography in the 21st Century?

- Could a photography exhibition change the way we look?

Why Janus?

Janus was the double-faced god of beginnings, endings, gates, doorways, passages, time and transitions. In houses he was often put facing external doors to protect the household from disasters. In the Pompidou Centre, that very visible, endlessly photographed example of post-modern architecture in Paris, the images on both sides of a board hanging in the central market hall are those of President Pompidou. Facing in opposite directions, they signify a transition or passage from the modern to something beyond it. When it was built in 1970, one of the principal architects, Renzo Piano, said that the design concept was based on a medieval market place where, on the interlinked and intersecting layers of spaces, people would meet and talk. So we have a paradox of an ultra-modern expression using a medieval concept as a vehicle to ring in the revolution-avoiding socio-political changes so necessary in France post May 1968.

The digital age and consumerism:

In his documentaries entitled “The Century of the self,” (2002) Adam Curtis illustrates how the consumer-led policies of the early 20th Century are still in place today in the USA and in the rest of the industrialized world. The series focuses on how the work of psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud was used by business and politicians to read and fulfill created desires to control the masses, develop consumerism and how people saw themselves. The prime protagonist in the series is Edward Bernays, Freud’s nephew, who picked up on Freud’s contention that people are irrational and that if you pander to their selfish desires, tap into their deepest fears, in every field, they become docile and malleable. Furthermore, if you could link a product to their emotional desires and feelings you could persuade people to behave irrationally believing that they felt better for buying a certain product. The late 1920’s saw the flourishing of consumerism in the USA, the start of political spin and the commodification of Hollywood and its celebrities, and the Wall Street crash. In an interview following the death of Marilyn Munroe in 1962, playwright Arthur Miller maintains that rather than freeing man, consumerism was controlling and defining him and that it was part of the power-mad ideology of the times.

Elaine Glaser, author of Get Real: How to see through hype, spin and lies of modern life states “ When every person in a train carriage is staring at a small illuminated device, it is an almost tacky vision of dystopia. … Technology – along with turbo-capitalism – seems to me to be hastening the cultural and environmental apocalypse. The way I see it, digital consumerism makes us too passive to revolt or to save the world.” This illustrates precisely what Bernays was trying to create in the 1920s, and what debord maintained regarding the character of the spectacle. To complete the picture, in the 1950’s, Theodor Adorno wote in The Dialectic of Enlightenment: ‘Not only do we have the freedom to choose what was always the same, but, arguably, human personality had been so corrupted by false consciousness that there is hardly anything worth the name any more. “Personality,” they wrote, “scarcely signifies anything more than shining white teeth and freedom from body odour and emotions .’(Jeffries)

Digital imaging relevance:

In his 2013 publication, Martin Lister includes the essay “The digital image in photographic culture” by Rubinstein and Sluis in which they introduce the Janus principle :“Like a two-faced Janus, photography points in two directions at once: one side faces the objects, people and situations as they appear in the ‘real’ world, and is occupied with the representation of events by flattening their four dimensional space onto the two dimensional plane of the photograph … the other side points towards photography’s own conditions of manufacturing, which is to say towards the repetition and serial reproduction of the photographic image.” (Lister p. 25) This essay will show if or how this illustrates aspects of the digital self by identifying the transition moments and the ways in which the new medium has formed and adapted how we look, meaning both how we appear and how we see. The work used to substantiate the points made are the photography of Penelope Umbrico and Erik Kessells, the manifesto of the 2011 Rencontres d’Arles exhibition (Appendix 1) and the 2012 paper Selfiecity: exploring photography and self-fashioning in social media by Tifentale and Manovich (9).

How true is our digital imaging?

To Martin Heidegger in 1977 is ascribed the observation that “representation is the key characteristic of the modern age” in which “ the world becomes a picture and the human being becomes a subject.”(Lister p.25) Heidegger goes back to the 17th Century, to Descartes who maintained that representation was the marker of modernity because it concerned itself with truth founded on rational and abstract principles rather than on subjective or aesthetic ones. Descartes was talking in scientific terms where experiments could be repeated and the outcomes could be represented in diagrammatic form, without any subjectivity or aesthetics involved. In making the assumption that humans are rational and capable of objectifying the world of knowledge in graphs and diagrams, he makes us consider the converse, that humans can express themselves in subjective, aesthetic, artistic and metaphysical terms too. The ontology of photography has been based on the visual representation of the science of optics, the mechanics of automatism and the objectivity of rational representation. Logically, this all gave photographs, created by a rational human author, the credibility of having transferred reality from the object to its re-presentation. With the advent of digital photography, based on the binary system of computer language, we would expect that that scientific quality would sustain the idea of objective representation operated by a rational human to produce objective, credible, reproducible representations. This is supported by that sage of all photographic sages, Roland Barthes who states: “The photograph is literally an emanation of the referent. From a real body, which was there, proceed relations which ultimately touch me, who am here.” (Barthes, 1981:80). Those who are au fait with dark room photographic practices as well as with digital algorithmic capabilities, know that people are involved in the production of an image, be it on paper or on the screen and that the process, therefore, will involve more than just scientific, mathematical or rational principles.

Psychological implications:

Psychologist Dr Tamara Hicks claims in an article of 2010 that we all have a ‘digital mask’ to engage with the technological world. She goes on to identify the plethora of internet technologies which had been introduced and to which we can add so many others which surface daily under the conceit of digital culture. Hicks observes “… All of this technology has come at us so fast and furiously that we haven’t had the time to think about how our relationship with it shapes our very identity.”(PT) It seems, therefore that the ‘digital self’ is under constant change and that we, the ‘self’, are not aware of who we are any more.

Despite the fact that we know how we are being manipulated to keep capitalist fires burning, we continue to define ourselves, unwittingly perhaps, by the information we upload to all the sites of which we are subscribers. Do we know who picks up our information, where in the world or why? Not really. The groups we belong to on Facebook and other social media websites, the ‘private’ conversations on Whatsapp or Snapchat, the searches we make on the internet, the items we purchase online, the articles we post or repost or share on social media all become part of the complex algorithms which define our composite selves and ‘know’ us better than we know ourselves. All the information is fed to commercial enterprises which then target us using the information we have voluntarily given up. The ends are the means.

Rencontres d’Arles 2011 Manifesto:

Linguistic analysis:

The manifesto, written by Erik Kessels, one of the curators of the 2011 Rencontres d’Arles exhibition (appendix 1), reflects the style of the Futurist manifesto which appeared in 1909, and observers might be forgiven for thinking that the 2011 one is a parody of its predecessor. It is very assertive by marking the changes starting with the adverb and punctuation mark “NOW,” and “ABSOLUTELY PRESENT.” In the present , and the future by implication, things relating to photography are and will be different. The translation of the prose part of the 1909 Futurist manifesto reads: “With it, today, we establish Futurism, because …” (Italianfuturism.org).

The pronoun ‘We’ occurs in both manifestos and is emphatic in both. Although the ‘We’ in the 1909 manifesto refers only to one (Italian) man, Marinetti, the ‘WE’ in the 2011 manifesto refers to five European men, 4 of whom are established in the canon of professional photographers and one a professional curator. Given the background of the co-signatories of the 2011 manifesto, is it legitimate to feel that their ‘WE’ resents the intrusion onto their professional territory of every amateur Tom, Dick and Harry photographer using any conceivable image making product and scissors?

There is in both manifestos an emphasis of a separation from the past “WORK THAT HAS A PAST BUT FEELS ABSOLUTELY PRESENT”(Appendix 1.) “Our fine deceitful intelligence tells us that we are the revival and extension of our ancestors—…”(Futurist manifesto)

Is everyone a photographer now?

The curators have gone beyond the question ‘Is everyone a photographer?’ the photography equivalent of the 1975 Joseph Beuys poster “Is everyone an artist?‘’ because it states “ WE ALL RECYCLE, CLIP AND CUT, REMIX AND UPLOAD” which also implies that we have all gone beyond taking images, we now make images in a myriad ways and all under the umbrella of digital photography. Furthermore, in the introduction to the Arles 2011 catalogue, Clément Chéroux, curator of the Pompidou Centre and co-writer of the manifesto, claims that the importance of images has gone from ‘newness’ to ‘intensity’. In clipping and cutting (frivolous, reductive terms explaining how images are ‘made’ today), we are no longer stealing someone else’s work because the images are seen as collective cultural property and the astronomical numbers of images uploaded daily make the practice of sorting through them appear as an OCD, a madness, a loss of rational behavior taking away from the serious expertise, intentions and authorship involved in the original images.

Penelope Umbrico:

One of the artists on show at the Arles 2011 exhibition was Penelope Umbrico whose work is eye-catching and constantly evolving. She defines herself as “an artist whose subject is photography. …It has expanded beyond the field and there are very few boundaries –”(Martin 3.2) Her most famous work is Suns from sunsets on Flick’r which started in 2006 and is on-going as more sunsets are added to the website.

Figure 1:

Her work deals with the flood of images, in this case of suns on Flick’r, which are uploaded without any reflective or critical judgement. Through her work, Umbrico asks us to reflect on the role played by image making and image makers in an image-saturated world. Having claimed that, Umbrico goes on to make yet more images of the over-imaged which seems to contradict her initial premise.

Although in her MA thesis on Umbrico, Minjung “Minny” Lee writes about ‘visual ecology’ which, as she explains in a footnote, was a term coined by Juan Fontcuberta (also one of the Arles 2011 manifesto contributors) to mean “the activity of artists appropriating found photographs instead of making new photographs. This recycling of images actually helps the environment, as it does not take up any new server space.” (idem) . Is the space not doubled every time an image is appropriated because it now exists on yet another server space? Umbrico and Erik Kessels continue to make work that questions our online photography behaviour making us pause to think about what our actions show about us and about society in general, how our actions impact on our constantly changing perspectives on ourselves and society. As the manifesto implies, we can make limitless images which we can ‘share’ with the world and nobody can limit our production. There is no more need for the focus groups analysed in “the Century of the Self” because all the information needed by policy makers and corporate companies is there for anyone to use.

In using the grid format to present her work, Umbrico does not present a narrative we can read in sequence and interpret. Instead, the reading of the composition takes us beyond the limits of the grid frame to wonder where all these representations of suns are taking us and why we have this compulsion to make images of sunsets to then upload them. If there is an entry point into the sun grids it is not clear. What does it say about those who upload the images? Who are we collectively? How many ‘likes’ and ‘shares’ do we want for our images? Umbrico sees the abundance of visual information on the internet as “a visual index of data that represents our collective thoughts, ideas desires and so it is a constantly evolving and spontaneous auto-portrait.” (Martin p. 3) The more we interact with the media and the technology, “the more they function as indexical records.” (idem)

Erik Kessels:

The exhibition at the 2013 Rencontres d’Arles by Erik Kessels’ “24 hours of photos”, presented the same problem as Umbrico’s practice does. Kessels printed the million images which had been uploaded on to social media in a day and dumped them in a room of the Palais de l’Archevêché. Does this represent visual ecology too?

Figure 2:

My photograph of the Erik Kessels room at Rencontres d’Arles, 2013

The installation resembled an avalanche of images about to obliterate the viewers – do we go beyond admiring the idea and its execution?

Selfies: endless self promotion or brand advertising or is it the same thing?

The multi-disciplinary team which worked on the Selfiecity project in thirteen global cities, analysed the demographics, the poses and expressions of those taking them. A selfie, according to Oxford Dictionaries, is “a photograph that one has taken of oneself, typically one taken with a smartphone or webcam and uploaded to a social media website.” Jenna Wortham of the New York Times calls them “a “virtual “mini-me,” what in ancient biology might have been called a “homunculus” – a tiny pre-formed person that would grow into the big self.” (7). Also relevant to this essay is an attitude of Karen Nelson-Field, author of Viral Marketing: The Science of Sharing (Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press, 2013): “We now all behave as brands and the selfie is simply brand advertising. Selfies provide an opportunity to position ourselves (often against our competitors) to gain recognition, support and ultimately interaction from the targeted social circle. This is no different to consumer brand promotion.” (7) Debord would simply say QED at this point.

Apart from falling prey to the self-promotion, self-revealing ploys of online quizzes and other ‘fun’ social media activities, selfies express in current technological form what pen or paint portraits did in the past and reflect the revolution in snapshot photography for the masses associated with the Kodak Brownie camera introduced in February 1900.

In a dossier on the selfie in the 2014 January-February edition of Fisheye, it states that ‘selfie’ was first used in 2002 on an Australian online forum, and the ‘♯selfie ‘ in 2005 on Flick’r, but its usage did not take off until 2012 and accepted in the online Oxford dictionary in 2013. The same article states that celebrities are a step ahead of other mortals and quotes Justin Bieber who ‘selfied’ his tattoo, his six-pack, himself with a groupie, with his blond girlfriend … until eventually, the article states, “The singer quickly understood how to make people talk about him and how to make business.” (Fisheye p. 27 – my translation) In 2013 he invested $1.1 million in the app ‘Shots of me’ which allows users to make, to share, to like and to geolocate images of themselves. Kim Kardashian (10) also posted advice, it states, on how to take the perfect selfie … with pout. Last year she published a 448 page book of her selfies which sold 125,000 copies in the first three months. ( 11).

Figure 3:

Kim Kardashian selfie with pout:

Tumblr joins the circus with sections on selfies taken in serious places like at funerals (Obama, Cameron et all at the funeral of Nelson Mandela) and in front of books in a library.

Conclusion:

The passage from old to new in photography seems to have been marked by, inter alia, the 2011 Arles manifesto reflecting a decisive shift to the ‘cut, clip, remix and upload’ (appendix 1), where you no longer needed to be a professional photographer but its pejorative ‘a species of editor’ (Appendix 1) to show your photographic work to the world. This work ‘that feels like play’ like that of Penelope Umbrico, exhibited at Arles in 2011, has a serious critique of those unfettered practices lacking self-checking controls. Does the supposition that it feels like play mean that it lacks the gravitas of previous photography? The acceptance of the word ‘selfie’ in the Oxford dictionary in 2013 gives legitimacy to a practice which confirms unbridled digital self-promotion apparent on social networks which, sustained and abetted by new technologies, replicates and sustains those advertising practices started in the 1920s by Edward Bernays. Commerce sees the ‘homunculus’ grow, in certain respects, daily, as do their profits.

It seems that the period between 2011 and 2014 was pivotal in photographic history when change set in; when social media, engendered by technology, allowed digital practices to mark a shift in people’s online behaviour and when selfies did not constitute our only indexical selves. It also signifies a time during which corporate companies adapted to these changes and continued using consumer profiles to boost sales. Unable to resist consumerism and conformity, whether seen as a rational Cartesian being or an irrational, fear-ridden Freudian consumer, the self occupies centre-stage in representations of the world, regardless of audience, and becomes its principal subjected end-product. The digital self is branded by capitalism, time, technology and social media.

Janus, an all-seeing mythical, irrational god, still stalking our post-modern world, would not take or make selfies, in my opinion. As a god, he does not need to promote himself, he does not need to fight for supremacy in his community of one, his status never changes. As such, he does not need our ‘like’ or ‘share’ or the subjective aesthetics of Kim Kardashian, she of the (absence of) white teeth and free of body odour, to boost his self-image. Can he of ancient Rome protect us from our cultural apocalypse?